Perhaps a decade ago, as part of my role as Chair of Composition at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, I organised a regular seminar for all the composition students.

One week, I walked into the teaching space and noted there were 6 exceptionally talented young women sitting together amongst the cohort. (There were more than 6 women in the room – but these were exceptional in my estimation.) I took them aside before the class started, and said to them, “You are all immensely talented. Women are underrepresented in music composition. If you agree, I would like to support you to achieve the highest you possibly can, including providing opportunities for your works to be heard and workshopped.”

This informal “hot-housing” approach seemed to work, judging from the young women’s progress. A few years later (2015), I suggested to the Dean, Anna Reid: what if the Sydney Conservatorium instituted a formally designed program within a postgraduate degree, directed specifically at women to try to address some of the systemic problems they faced?

What if the participants were enabled to write music for a range of professional musicians and ensembles in an unprecedented way? These musicians and ensemble directors would get to know the composers and their work: an important side-effect that may have positive effects on career progression into the future.

Anna was receptive, so I designed it to be a two-year program. The reason for this was that the participants would write a piece for a musician or ensemble in the first year, and then do the same again in the second year, thereby having an opportunity to take what they have learned and re-apply it. There are too many one-offs in the composer development space.

Research shows that role-modelling is extremely important to educational experiences. There were many excellent potential mentors who could help to guide the women on projects, such as Maria Grenfell, Moya Henderson, Anne Boyd, Elena Kats-Chernin and Natalie Williams. It would be fine for me to direct the overall program, but a lot of the nitty-gritty should come from successful women rather than a bloke.

I didn’t want the program to just be an artistic training opportunity. I remember reading a comment from Dr. Sally Macarthur from Western Sydney University that women weren’t being taught business and networking skills to the same extent as men, and were thus at a disadvantage. The classical music industry does rely in large part upon connections.

So what if we aligned the artistic, creative and musical side of the program with mentors from the business side of things, giving the participants the chance to use these skills to their advantage. Would this be helpful to the composers?

The following document was prepared for Anna Reid as a first draft for the program, dated 31 March 2015.

As can be seen from the above document, we were aiming to work with a terrific range of musicians and partner organisations at the highest professional level. There are a full set of important skills learned from this sort of collaboration that go beyond the typical university experience of writing for student performers. In the first iteration of the program, Claire Edwardes, Sydney Philharmonia Choirs, the Goldner String Quartet and the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra all enthusiastically agreed to be a part of the project. They are all incredible musicians for whom any classical-tradition composer would be delighted to write a new work (or two).

In planning this project, I consulted with current female composition students of the SCM (Sydney Conservatorium of Music) to get their opinions on the value of such a program. It was an interesting discussion. There was certainly enthusiasm for the composition activities, “Wow! Writing for the Goldner String Quartet? AND the TSO?”, and also for business skills training as well. But some expressed reservations that they would have been selected on their gender rather than on their merit. I recall responding, “Change is coming, and so this is an opportunity for you to be part of what’s ahead, and to take the opportunity that is offered – if it’s not you, it will be someone else.”

The support of the Dean of the SCM, Prof. Anna Reid, was critical in getting this all happening and approved. It could not have come about without her.

Its first iteration had the clunky name of the “National Women Composers’ Development Program” (NWCDP). I considered “Composing Women”, but was aware of a festival of the same name in the 90s run by Becky Llewellyn, and didn’t want to be a man erasing previous women’s achievement.

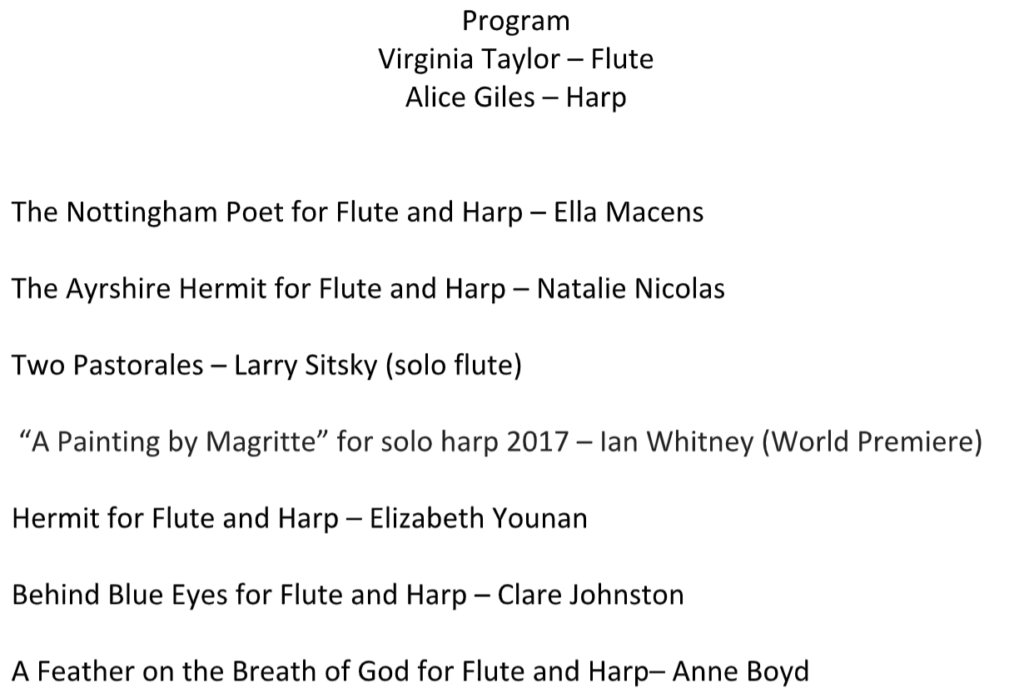

The inaugural program was a tremendous success. The four students worked terrifically hard, wrote lots of fantastic music – including for some extra opportunities that were not part of the original brief, such as a new work for the Canberra Symphony Orchestra’s Australian Series for flute and harp.

One of the most pleasing aspects of this program, besides the individual musical growth of the composers, was the flow-on effects for each of them. Before they had even finished, each composer was taking advantage of an increased range of opportunities, such as a?workshop with the Flinders Quartet in Melbourne, or being the first Australian composer to be accepted to study at Curtis University in 100 years. Each of the composers has gone on to do remarkable things (see their websites: Ella Macens, Natalie Nicolas, Clare Strong, Elizabeth Younan) – testament that the approach worked.

After the initial success of the program, it was clear we had to run it again. However, for its second iteration we were extremely fortunate to have Professor Liza Lim join us as the Sculthorpe Chair of the Sydney Conservatorium of Music. It made sense for Liza to take over the leadership of this program.

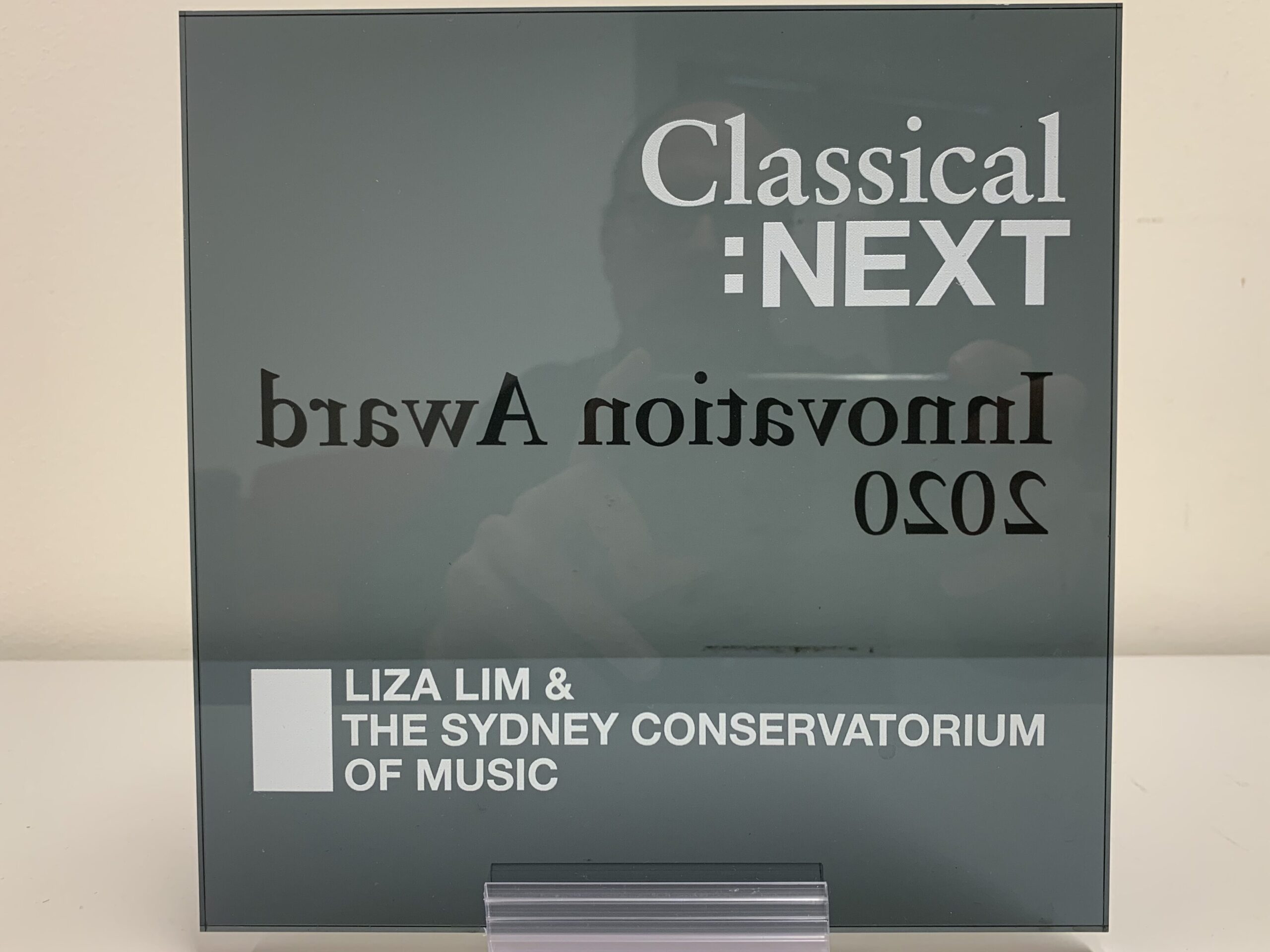

The fundamental structures stayed the same: a group of four women selected to undertake high level work with top-performing ensembles around the country (and in this case, internationally), with students in 2018-2019 writing for American flautist Clare Chase. The students in this cohort wrote a new work for Sydney Chamber Opera: a massive achievement by them, and one that won critical acclaim – including for Peggy Polias whose opera won the Dramatic Work of the Year in the 2021 Art Music Awards. The name of the program was changed to “Composing Women” and it’s been known as such ever since. The program & its director, Liza Lim, even won an international Classical Next award for innovation in 2020,

“…for being the only higher-level composition programme for women demonstrating a sustained, strategic commitment to change.”.

After two successful cohorts run by Liza in 2018-2019 (Josie Macken, Peggy Polias, Bree van Reyk and Georgia Scott) and 2020-2021 (Brenda Gifford, Fiona Hill, May Lyon and Jane Sheldon), the decision was made to cease the program. Why? And specifically, why if it had made such a difference?

“The program has created a significant cultural ripple effect in the classical and art music world. We haven’t done it alone – which is really important – change only sticks when everyone comes along,” said Professor Lim.

“But now, no organisation can say that they’re future oriented or relevant to contemporary society without women’s presence.”

Quote from Liza Lim on the conclusion of the Composing Women program

Things have certainly changed from 2015 to 2022 in the support and prominence given to female classical composers in the Australian context. Liza’s thoughts were that enough had changed in the consciousness and engagement of women as composers by organisations, ensembles and musicians interested in contemporary music that a program like this was not as needed as was previously the case – and that the resources of places such as the Sydney Conservatorium could be directed elsewhere. As an example of this, the SCM started its Equity in Jazz program, headed up by Jo Lawry – it’s certainly true that gender equality in the jazz area is a fair way behind that of classical music composition. We also have been discussing other areas that would benefit from such targeted support.

So, what has been learned from the Composing Women program?

Most importantly: if a problem has been recognised, and if stakeholders wish to make a change, there needs to be a significant, long-term investment, rather than a one-off opportunity. The two-year program is a model that works. The Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra has adopted it for the Australian Composers School and it works very well there, too.

In the general case of composer development, there are two ways to get high-quality contemporary music. The first is to wait for the next Mozart to come along. (Good luck with that, I say!) The other approach is to invest in training in a significant, long-term way. Provide opportunities for composers to try things out, to get things wrong, to fail. This is a contentious approach because musicians’ time is valuable (and expensive). A classical orchestra can program a Brahms Piano Concerto that we know from more than a century’s performances will be amazing. Indeed, current composers should stand on the shoulders of those who went before. But there is more to establishing an innovative, contemporary career as a composer writing fantastic music than this. Composers need the space, the time and the opportunities to learn from other musicians in a practical way. Excellence doesn’t appear out of nowhere, or from just reading a textbook.

If we – musicians, the arts industry and audience members – want the classical music sector to develop and grow, long-term programs can contribute to serious cultural and musical change, as Composing Women successfully did.