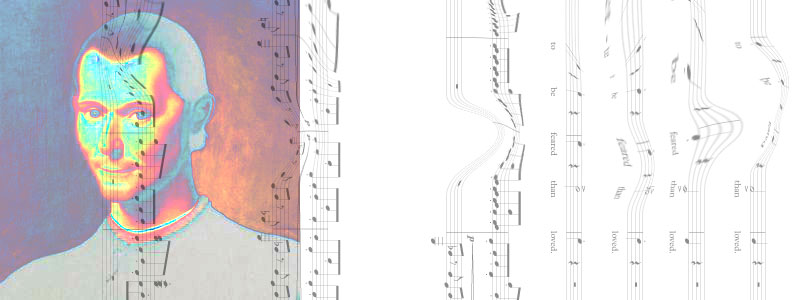

I have completed a new, large work for the Sydney Philharmonia Festival Chorus and the Sydney Youth Orchestra, which will be premiered in the Sydney Opera House on 8 and 9 October, 2014. The lyrics come from the writings of Niccolo Machiavelli, whose image is placed above this post.

Following are the program notes. Or go here for information from Faber Music on the instrumentation and choir sizes.

—

There is nothing quite like singing in a choir, as so many people in Australia and the world know so well. Even more special is singing in a massed choir of 400+ voices. In performance, each chorister combines to create such a powerful sound to raise the roof of a venue like the Sydney Opera House.

This year I was commissioned by the Sydney Philharmonia Choir to write a new work for massed choir and orchestra. When I say the Sydney Philharmonia Choir, I really mean the members of the Sydney Philharmonia Festival Chorus. Many of the singers in this group put forward their own hard-earned money to enable the construction of a brand-new piece of music.

Talk about putting one’s money where one’s mouth is! This is really crowd-funding at its best. So when I set out to write this new piece, I was imagining each of these choristers producing sounds, phrases and melodies that, if not for their own foresight and generosity, would not exist.

When writing new choral or vocal music, the starting point for the actual music is usually the text. Good text will dictate its own rhythm, and indeed sometimes the music itself.

Another starting point for me was contemporary events and society. To me there isn’t much point in writing music that isn’t relevant to contemporary musicians and audiences. Especially when lyrics are involved to make the intention very clear.

So after a long search, and given what’s been going on in Australian politics recently, the writings of Niccolo Macchiavelli (1469-1527) were the best choice. It may seem strange to use texts from 500 years ago, given what I say above. But how can one go past such choice quotes as:

“It is better to be feared than loved[, if one cannot be both]”;

“Politics have no relation to morals”, or even:

“The promise given was a necessity of the past, the broken promise is a necessity of the present.”

Did Machiavelli has a crystal ball to see into contemporary Australian politics when writing the above gems? Or is it rather something more fundamental to the human condition?

In the end then, It is better to be feared than loved (the title of my new work) deals with contemporary politics of governments, politicians and the pursuit of power. As such, it is often musically bombastic and overblown – which was tremendous fun to write.

And, I hope, to sing.